Read Ivan Garcia on TranslatingCuba.com

Or you can read all of Ivan’s posts by clicking here.

Readers: Given the explosion of writers now being translated by TranslatingCuba.com, to make our work manageable and as a convenience for our readers, we are consolidating all the posts on one site.

Translators: YOU CAN HELP! Please go to HemosOido.com to translate Ivan and others.

How a Havana Couple Lives on Cuban Pesos / Ivan Garcia

The photo is not of Yesenia and Sergio. It is another of the many couples in Havana who, lacking resources, go fishing with their daughter and dog. Taken from Hablamos Press.

Ivan garcia, 26 January 2016 — In the large commercial centers of Havana, whether Carlos III, Galerias Paseo or the at Avenida Boyeros and Camagüey Street, you will not find families like Yesenia and Sergio.

In these ’shoppings’ or hard currency stores, a no-name plasma TV costs 399 CUC, or 10,000 Cuban pesos at the exchange rate of one Convertible peso (CUC) for twenty Cuban pesos (CUP). A juicer costs 219 CUC, or 5,475 Cuban pesos, and a food processor 118 CUC, which is 2,900 Cuban pesos in the devalued national currency.

Between them, Yesenia and Sergio earn 1,800 Cuban pesos a month, about 43 CUC. That amount of money does not allow them to buy modern appliances or a third generation computer. They can’t even sit in a state-run bar and have a beer together.

Six years ago they married, and in 2015 she gave birth to a boy, now about to celebrate his first birthday. This is not about two lazy people subsidized by the State, or people with no skills.

Sergio is a civil engineer and Yesenia graduated in art history. They live in a two-bedroom apartment in La Vibora neighborhood, in the southern part of Havana. At their respective jobs, neither has resorted to “inventing” (that is stealing State resources). Nor do they have family in Miami sending them 100 dollars every month.

How do they manage to make ends meet? Let’s look at this couple’s daily life.

Sergio gets paid on the 10th and Yesenia on the 22nd. Meanwhile, on the national television news the presenters describe in detail statistics and production figures for an economy that never stops growing, but the couple doesn’t even notice. They are two busy doing their accounts on a Chinese-made calculator.

“We have a budget of 250 Cuban pesos a week. And 80 pesos for incidentals. We pay 60-80 pesos a month for electricity. The home appliances we have are a Chinese-made Panda TV (ancient, with cathode tubes), two fans, a fridge, blender, rice cooker, iron and an old Russian washing machine,” says Sergio.

He explains that to save electricity, “we only use the rice cooker once a day — it uses a lot of electricity. I’m always at my wife not to leave the lights on. What we use the most is the TV, because there are not many opportunities for recreation, we are always glued to the TV.”

According to the National Bureau of Statistics and Information (ONEI), the average monthly salary in 2014 was 584 Cuban pesos, 197 pesos more than 2006, when it was 387. In 2015 it “grew” to 600 Cuban pesos.

But the nominal growth of government wages hasn’t kept up with the purchasing power of this income, because prices have risen over the same period. ONEI statistics include interesting data about the wage distribution in Cuba.

In 8 of the 16 provinces, the workers have an average salary below the national average: Isla de la Juventud (530), Santiago de Cuba (540), Guantánamo (548), Artemisa (551), Mayabeque (553), Granma (565), Camagüey (566) y Holguín (575).

The sectors with the lowest salaries are Hotels and Restaurants (377 Cuban pesos, which is why the employees steal so much), Public Administration, Defense and Social Security (485), Culture and Sports (486). The best salaries are in the Sugar Industry (963), Mining and Quarrying (819), and Science and Technological Innovation (811)

Those who earn the most are paid 40 percent more than the lowest average salary. Those depressed wages drown families like Sergio and Yesenia.

“It is impossible to live on your salary alone. The food from the ration book only costs 35 pesos a month for three people, but with what you get in the ’basic basket’ you can’t live, much less if you have a baby. For fruits, vegetables, rice, chicken and pork we spend close to 900 pesos a month. With the hundred-odd pesos left over after paying the light bill, we have to pay for gas, water and transport. When our son is sick or some appliance breaks, we have to dip into our reserve or the extra money we keep in the cupboard,” says Sergio.

How can they get extra money? “I tutor elementary and high school students in math. This way, under the table, I get about 40 chavitos (CUC), more or less two people’s salary. This hard currency goes to buying oil, toiletries, cereal, jam and juice for the boy. All in all we lead a very hard life,” he confesses.

Despite living 85 miles from Varadero, they don’t know “the most beautiful beach in the world,” according to the government’s tourism ads. They can’t even dream of a weekend in a three-star all-inclusive hotel.

What are Yesenia and Sergio’s future plans. The couple takes some minutes to respond.

“In Cuba the future is the next day. Clearly we want our son to grow up healthy and well-fed, to buy him clothes, shoes and toys, to sleep in a room with air conditioning, to get a car, visit another country, and when we go to the Havana International Book Fair to be able to buy as many books as we want, we are passionate readers. But right now we are denied all this. I want to be optimistic and think that things will change. The question is when,” says Yesenia.

Have they thought of leaving Cuba? “We don’t have family abroad, nor the money to pay for the risky journey through Central America. We don’t have any choice but to endure the storm on the island. For people like us, the miracle is to be alive.”

Abuses of Cubans Inside and Outside the Island / Ivan Garcia

The paper says I am sending you a beach game! (Similar to horseshoes) And this is sand! // It seems that first they want to send you the beach. (Pitín cartoon taken from Un paquete de disgustos)

Iván García, 30 January 2016 — After the American Airlines pilot made a perfect landing with the Boeing 767 on the Terminal Two runway at the José Martí International Airport in Havana, the passengers broke out into applause.

Gisela Mirantes could not contain her tears. “I haven’t come to Cuba for ten years. I am from Pinar del Río and live in New Jersey. I have heard that things have changed for the better here”, she said, before going down the steps to the customs area.

That’s when the tragedy began. Lacking any information, Mirantes had brought three televisions and the same number of PCs. And dozens of presents, domestic appliances and clothes for her poor family in Vueltabajo, all in bulky packages.

“Things are just the same, or worse. Those people in customs are shameless. They charged me $250 for excess baggage, in spite of the fact that in Miami I had already paid this charge to the airline. Then I had to pay $1,200 for bringing a third 42 inch television, because they only allow two televisions and one computer”, she told me angrily, while she was waiting for a taxi on a platform, more like a railway station than an airport.

Raise your hands, any traveller who has not been subject to harassment at the Cuban customs. You are hardly ever received with a smile. They go over your baggage like police frisking a criminal.

The air terminal workers openly offer travellers, arriving or departing from Cuba, to buy or sell dollars in a parallel market. After taking your money and charging an extortionate amount in duties, you get to a window where they exchange your money.

It is a legal casino. Cuba is the only poor third world country where, in spite of having two currencies which don’t float in the foreign exchange markets, they artificially value the Cuban convertible peso (CUC) higher than the US dollar.

“It’s daylight robbery. I came with my wife and children to spend a vacation and they gave me 2,690 convertible pesos for $3,000. Before I have even bought an ice cream I have already had to pay tax”, I was told by a Puerto Rican living in Tampa.

The ridiculous measures taken by Cuban General Customs, who impose duties on things you bring in and have to be paid in foreign currency if you travel more than once a year, make Cubans angry.

Even medical volunteers working in remote locations in the Brazilian Amazon don’t escape. “The government doesn’t even take into consideration that we doctors are the ones that contribute the most foreign currency to the economy. Not satisfied with grabbing more than half of our salaries, every time we return to Cuba we have to leave a large part of our money with Cuban customs”, complained Obdulio, a doctor going to Brazil.

In order to write this report, I tried to talk to a customs official so that he could explain to me why the Cuban state levies such extortionate duties on articles or goods that people bring here to improve the quality of life of the people.

“We don’t give quotes to counter-revolutionary journalists”, someone blurted out at me before hanging up the phone.

The problem is that these measures don’t just affect the “counter-revolutionaries”. Ernesto belongs to a unit of the Communist Party in Old Havana.

Twice a month, his daughter sends him parcels from Canada. “The post only accepts a kilo and a half free of duty. Just think, this weight is equivalent to a pair of mens’ shoes. My daughter sends things to the whole family. For any weight over a kilo and a half she has to pay 20 CUC per extra half kilo. Once she had to pay 80 CUC for one box”.

Camilo, an economist, considers that maintaining these stupid policies on duties and exchange is inappropriate in relation to the newly-revived relationship with the United States.

“Above all, it affects Cubans. Apart from medicines, the customs levies duties on everything over a kilo and a half, including on goods brought by Cubans who travel twice a year. If they want more American tourists to visit Cuba, they should change the dollar-convertible peso exchange rate. It’s a joke that the chavito (CUC) is valued higher than the dollar. This puts a brake on what tourists spend”, Camilo adds.

Apart from the high duties, there is the theft of articles in the airport and the stores where they keep the postal parcels. “And the inadequate handling. They broke the screen of my television by moving it carelessly. Neither the customs nor any other department paid for the damage”, Vilma, a Cuban American, told me.

Right now, three items of news raise the hopes of people on both sides of the water. It is hoped that this summer there will be regular American flights to the island, it is rumoured that the cost of a plane ticket will drop by 30%, and you won’t pay the arbitrary $422 for a return trip of 45 minutes, and that a ferry will start between Havana and Florida.

But, up to now, the Cuban authorities are not considering any reduction in duties, in the landing fees, or any other measures which could help bring down the cost of travel to Cuba. Although the ferry would allow passengers to carry up to 200 pounds each, it seems that the duties will remain as they are.

It is the Castro regime’s silent and effective “blockade*” on its own people.

*Translator’s note: The Cuban government calls the American embargo against Cuba “the blockade” even though it is, technically, an embargo.

Translated by GH

Cuban Education in Free-fall / Ivan Garcia

Ivan Garcia, 21 January 2016 — Seven in the morning on a weekday. After a frugal breakfast of bread and mayonnaise and an instant powdered drink, Yamilka Santana, fourteen years old, puts on her backpack, weighing a little over 12 kilos.

She isn’t going on a trip, nor is she going camping. She is going off to her junior high school, Eugenio María de Hostos, in la Víbora district, a thirty minute drive south of Havana.

“I am taking all my books and exercise books in my backpack, as we don’t yet have a timetable for our classes. There are about twenty notebooks. Also, a snack, a lunchbox, and a sunshade. It looks as if I am going on a journey abroad”, Yamilka says, smiling.

About 350 pupils study in her school. They need to stay in school from eight in the morning until twenty past four in the afternoon. The state does not provide them with a school breakfast. Nor lunch.

It only gives them a snack, which most of the kids don’t eat. “It’s rubbish. Bread and a hamburger, which has a strange taste, or horrible potato croquettes. The bread is almost always hard and old. You have to be really hungry to be able to eat it”, says Melissa, a seventh grade student.

The school patio where they line up in the morning is uneven. In a wide area, previously used for sport, there are no basketball backboards and the smooth-finish concrete surface is lifting.

When it rains, the water penetrates the walls and the roof. “You get more rain inside than outside. When you get heavy downpours, they suspend classes”. says Josuán, from the ninth grade.

More than a few parents have complained to the school. “It’s dangerous for the kids. They haven’t carried out any maintenance to the school for years, and one day the roof or the walls could collapse and that would be a tragedy. The government should be concerned about the bad state of most schools in Cuba”, says Magda, mother of one of the pupils.

But the complaints have had no effect. The government’s response is to paint the fronts of the schools with a coat of cheap paint. The teaching materials are insufficient and are deteriorating.

“Ten-year-old books are passed between pupils. There aren’t enough for everyone. I share a book with two or three kids. The notebooks, pencils and school supplies hardly last a term. Parents have to pay for the rest of the things out of their own pockets”, a teacher from Eugenio María de Hostos tells us.

The first problem the parents and families of the children and young people who are studying have to deal with is the uniform. In Cuba, uniforms are compulsory up to pre-university and degree courses.

Every other year, the state sells two uniforms per student. “But they screw you. They almost never have the right sizes. And you have to go to the market, where they charge you 5 convertible pesos for a uniform, which is equivalent to 125 Cuban pesos, five days’ pay. Some families get them, much better made, in Miami, explains Berta, mother of two.

In primary school, skirts, shorts and trousers are a wine colour, and blouses and shirts are white. In secondary, mustard yellow with white blouse or shirt. In preuniversity, blue. Technical education has ochre coloured uniforms. Nursing and medicine students wear white blouses and shirts and violet skirts and trousers.

Twenty six years ago, when Fidel Castro’s Cuba was subsidised by the Kremlin, public education in the island guaranteed snacks and lunches for students.

Also, two uniforms a year, a pair of school shoes and sport shoes for physical education. That was when a proud Castro repeated in his lengthy speeches that Cuban education was among the best in the world.

Now, parents have to buy the sneakers and snacks, which accentuates social differences.

“In spite of the fact that the school management asks families to avoid any ostentation, there are clear inequalities. There are students who come with sports shoes costing 100 CUC or more. Tablets, smartphones and even first generation laptops. They also bring good snacks and lunches. Others feel bad. With patched up tennis shoes and only eating bread and oil”, the director of a school tells us.

Up to the date of writing, no primary, secondary or pre-university in Cuba has an internet connection, producing backwardness in the use of information technology, which has a negative impact on the younger generation.

“We have adolescents who arrive at school, never having used a computer and never having surfed the internet. That is fatal in the 21st century”, comments Richard, a computing teacher.

But if the shortage of decent equipment and adequate food is notable in Cuban schools, the free-fall in the quality of education worries parents a lot. From their already battered domestic finances, they have to pay for private tutoring by experienced teachers.

“I pay 4 CUC a week to the retired teacher who gives my daughter tutoring, 16 convertible pesos a month, nearly half my salary. It’s a big sacrifice, but I do it not just so that my daughter gets good marks, but also that she builds up her knowledge and will be able to take a university course”, says Magda, referring to a seventh-grade student.

The deterioration in the quality of public education in the island is reflected in rude behaviour and in an alarming reduction in adolescents’ and young peoples’ level of culture. They hardly read or learn at all.

“We have not yet caught up with the 21st century. If we keep going like this, most of our current students will not be able to adapt to the requirements of the modern world. We are twenty years behind in terms of modern teaching methods”, explains a retired female teacher.

Very few people in Cuba want to be teachers. Low salaries and poor social standing are among the reasons. Many qualified teachers prefer to work as porters in five star hotels, as taxi drivers, or making pizzas in private restaurants. Or to emigrate.

Photo: from El País de Colombia.

Translated by GH

Opposition Marchers Should Change Their Strategy

Ladies in White and dissidents in Gandhi Park on Sunday November 22, 2015. Snapshot by Arturo Rojas, taken from CubaNet.

Ivan Garcia, 13 January 2016 — There were more than seven thousand arrests of dissidents in 2015, with most detentions lasting several hours. Beatings, harassment, acts of repudiation and degrading treatment by police are common in Cuba. Political reforms are not part of General Raúl Castro’s agenda.

Despite the repression in Havana there is one city block where democracy is respected. It was not a gift from the regime. It was a victory achieved by the Ladies in White in the spring of 2010. In this area you can protest and march without being brutally assaulted.

It is located in the Miramar district in the western part of the city. A procession takes place from Fifth Avenue and 26th Street, where St. Rita of Casia Church is located, to a park located on Fifth Avenue between 22nd and 24th streets, a spot formerly known as Prado Park in honor of the Peruvian dignitary Mariano Ignacio Prado and now known as Mahatma Gandhi Park.

After the march a brawl breaks out. Every Sunday at eleven o’clock for eight months State Security has been mounting an intense sting operation in the streets adjoining Fifth Avenue.

Dozens of boorish officers on Suzuki motorcycles from a squad known as Section 21 — a group conditioned to strike first and ask questions later — wait for the demonstrators at intersections or at a bus stop located at 28th Street and Third Avenue.

Every Sunday three or four buses are commandeered from the decrepit public transport system to forcibly transfer the Ladies in White and other dissidents to jail. A phalanx of police cars, an ambulance and cameramen from special services, who are there to film the uproar, round out the scene.

Among those mobilized are civilians from the so-called Rapid Response Brigade, a varied battalion made up of retired veterans, members of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution and guys inclined towards criminal behavior.

It is not unusual for the regime to employ an enraged mob to deal with what it considers to be “provocations.” The atmosphere on Sundays in this peaceful neighborhood in Miramar is similar to the chaos caused by radical baton-wielding hooligans at soccer matches in Argentina.

The basest instincts come into play. Sticks, metal rods and stones are used to assault compatriots simply because they think differently. The methods are violence, humiliation and verbal lynching. The festival of derision is repeated on subsequent Sundays.

The slogans of these paramilitary groups should strike a palpable fear in anyone who hears them. “Machete them; there aren’t many,” goes one. “Ready, aim, fire” and “mercenaries” are some of the other choruses sprinkled with crude expletives. You can disagree with a political organization’s stategy, but coarseness and intimidation should not be the solution.

Civilized governments put a premium on dialogue and respect. Clearly that is not the case here. On a list published by Reporters Without Borders, the island ranks 169th out of 180 countries in terms of press freedom.

Cuba is the only country in the Western world where all political parties, other than the Communist party, are prohibited. And when it comes to human rights, the regime approves only of those by which it abides.

For the military-run government human rights consist of universal public health and eduction, and access to culture and sports. No one would argue that these are not inalienable rights.

But lawful political participation, freedom of expression and freedom of association are rights too. It is a question of whether one perceives the glass as being half full or half empty.

As justification, Castro supporters claim to be under siege, stalked by the United States and choked off by an economic embargo. I don’t buy it.

The conduct of the rulers and their henchmen, handing out punches and imprisoning dissidents, is the result of a genetically predisposed hostility towards democracy. Transparency, dialogue and respect for differences are not part of the political strategies of the Castro dictatorship.

Nearly forty Sundays after the Ladies in White and the Forum for Rights and Liberties — headed respectively by Berta Soler and Antonio Rodiles — began their marches and petitions, the regime’s stance remains unchanged.

The dissident community itself is divided over how to proceed. Some believe that Soler and Rodiles should not be directly challenging the irrational ferocity of the special services and so they do not join in.

The international press barely covers the Sunday beatings and the Western democratic community is concerned with issues that it considers more important. At best, a spokesperson for the White House or the State Department might issue an inconsequential press release.

The problem is not whether the demands by the Ladies or the Forum are reasonable or excessive. They have a right to peacefully protest without being harassed, and not just in a “democratic block” on Fifth Avenue in Miramar.

In my opinion, the dissident movement should consider other strategies. The news media loses interest when routine repression begins to seem trivial.

Unfortunately, the world of mass communication is now driven by excess. For example, if a headline appears in a Swiss newspaper, it is because a dictator or mafia chieftain has opened accounts in the country’s banks, not because its democratic system functions like a Swiss watch.

If there are no dead or wounded, or if an event involves fewer than ten thousand people, the world’s leading broadcasters and major news organizations will continue to ignore attacks against a hundred or so women and men marching peacefully in protest along a stretch of Fifth Avenue to Gandhi Park.

Rather than increasing the number of participants in their marches, the Ladies in White and the Forum for Liberties should take up causes of a populist nature about issues that affect everyone, such as demanding food at reasonable prices and reducing prices in hard currency stores.

Or improving the quality of life, constructing and repairing housing, finding a solution for the more than 130,000 flood victims who now live in makeshift shelters and guaranteeing an efficient public transport system.

Or raising laughably low wages, unifying the dual currency system, initiating a national debate on unchecked migration; launching a campaign against domestic and gender violence, and demanding the repeal of Law 217, which prevents our compatriots from other provinces from moving to Havana.

Petitioning the government to include Cubans under the new Foreign Investment Law and urging it to draft a law allowing Cubans living overseas to participate in national political life. Also, reducing taxes on private businesses, among other concessions.

The list goes on. The Ladies in White could be the spokesperson for those citizens who are now sitting on the sidelines. Changing the focus of their petitions could change the rules of the game.

What would be the government’s reaction? Presumably another spiral of violence. But with broader social demands they would gain supporters among Cubans who only have black coffee for breakfast.

Cuban Tourism: Are There Enough Beds? / Ivan Garcia

Ivan Garcia, 10 January 2016 — One month before their trip, José María, his wife and two sons from Valencia Spain made reservations through the internet for two rooms at the Hotel Riviera, which faces Havana’s seaside drive, the Malecón.

“There was no way to rent a car,” says José María as he sips papaya juice in the cafe of the Inglaterra hotel in the heart of Havana. “Our plan was to spend six days in the capital and a weekend in Varadero. Family friends had told us all about the island’s climate, its natural beauty and especially the people. But the reality was quite different.”

He lists the problems. “The airport was a nightmare. It was filthy, with a terrible odor, and getting through customs was impossibly slow. We could not rent a car at the terminal or in any part of the city. It cost us forty-five euros just to take a taxi to the hotel. The driver didn’t even turn on the taxi meter. The Riviera had reserved a room for us that had only three beds because they thought we were travelling with small children. There were no other rooms available. It was infested with roaches and the air conditioning barely worked,” notes the Spanish tourist.

The next morning they moved to the Inglaterra. “The service was just as bad and we had to change rooms twice,” says José María “In one room the water heater didn’t work and in another the TV was broken. And what you see outside the hotel is awful. Except for a portion of Old Havana, which is beautifully restored, the city is falling apart. Most people are friendly, but it’s frightening to see how many prostitutes and shady characters there are per square meter.”

The hotel at Varadero was better. “But the food in the ’all included’ plan was disgusting. The staff had no motivation. It was as though they were being punished,” says José María.

Experiences like those of this Spanish tourist and his family in Havana and Varadero occur often in Cuba. Tourism is the island’s third largest source of hard currency, behind the export of medical services and remittances from overseas.

In 2014 remittances totaled 2.7 billion dollars. Cuba has 62,000 hotel rooms and an additional 19,000 rooms in private homes and hostels.

After the surprise announcement of the restoration of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States in December of 2014, the influx of tourists grew dramatically. Estimates are that 3.5 million people will have visited Cuba by the end of 2015, an 18% increase over the previous year.

The regime is probably taking in more than 3.2 billion dollars. The outlook for tourism in Cuba is promising.

Projections are that 23,000 rooms will have been built by 2020. Gaviota, a corporation headed by military officials, alone plans to build 14,000. Currently, Gaviota is the fourth largest hotel chain in Latin America and is predicted to be the second largest in four years.

But the biggest challenge to the growth of tourism on the island is not a shortage of rooms. It is more an issue of poor management, lack of supplies, low productivity and lousy service.

Add to these problems an infrastructure that has not been adequately maintained. Ariel Terrero, a government journalist who reports on economic issues, wrote a short piece for Cubadebate on the shortcomings of the tourism industry in Cuba.

A university professor who specializes in tourism told Terrero that, in spite of the increase in the number of visitors, hotel occupancy is less than 60%. Why then are there no available rooms in what is currently peak season in Havana and Varadero?

It is a management issue. According to the reporter, a large number of rooms at the Havana Libre hotel are closed for renovation.

As Jorge, a receptionist, points out, “In hotels that have been in operation for at least ten years, fifteen to twenty percent of rooms are not being used because of repairs that take months to complete.”

Though the state has designated tourism a high-priority industry, the companies in charge of maintenance do not have the authority to import fittings, equipment or supplies.

“The money that the tourism sector brings in is controlled by the state. Hotels where there is a foreign partner or that are owned by reputable companies such as Melia operate with more independence,” says Sergio, the head of a resort maintenance crew. “The rest must get state authorization. And bureaucracy is so widespread that it takes up to ten months to repair the air conditioning or plumbing system for a group of rooms.”

Does Cuba have an adequate infrastructure to deal with a hypothetical growth of five million tourists in 2016 and 2017.

“I don’t think so,” says a former manager of the Gran Caribe corporation. “What happens is that in Cuba they only think about construction, not about allocating resources for future maintenance. A hotel is more than a room, breakfast and maybe a meal. These must be complemented with car rental services, high-speed internet, cultural programs within the facility and outside activities such as visits to museums, cabarets and historical sites.”

In a city like Havana — with bad roads that make it difficult to drive without GPS, without proper signaling at intersections, with few and slow internet connections and with a poor public transport system — the former director believes “it is difficult to get return visitors. Because the crux of this business is not to get people to come once; it is to get them to come back.”

If you go to sites like Tripadvisor, one of the things you notice is the large number of negative experiences reported by foreigners who have visited the island. Others like the Spanish tourist José María have already erased Cuba from their tourist maps.

Iván García

Cuba: Toys Only for Hard Currency / Ivan Garcia

Photo: Domestically produced plastic toys for two to three-year-old children for sale at shopping malls and hard currency stores for 11.25 convertible pesos (about twelve dollars), a sum that amounts to half a Cuban worker’s monthly salary. Photo by Jorge A. Liriano Linares, from the blog by Juan Carlos Herrera Acosta.

Ivan Garcia, 8 January 2016 — When Fidel Castro came to power in January 1959, one of the first things he proposed was doing away with the legend of the Three Wise Men. The government tried replacing the tradition, which originated in Spain, by offering rationed toys through its shops. Now it does not even do that. If you do not have hard currency, your children do not get toys.

Fifty-six years later, the tradition has returned, although not to all Cuban homes. On the eve of Three King’s Day, eight-year-old Lemay gets out of bed early. January 6 is probably the most important date in his life. He has revised his letter to Melchior, Gaspar and Balthazar three times.

Whenever Lemay saw a new toy, he would erase one toy from his list and add another. Last week he became angry with a friend in the neighborhood who joked that the Magi were his parents.

“It’s a lie,” explained his father. “What happens is that, if you misbehave, they don’t bring you toys.” He takes out a letter with childlike scribbles written by his son on a sheet of paper from a school notebook. The proud father reads it aloud:

“Dear Wise Men: I was very good this year and I got very good grades in school. I would like to ask if you can bring me a bicycle and some inline skates. Also a football and anything else you think I deserve.”

For his family, Lemay’s toys are “an issue of national security.” He is an only child and all his relatives — those who live in Cuba and those live on the other side of the pond — get involved months before the holiday.

“We have been saving money from our remittances. His grandparents in Miami can’t use a ’mule’ to send him the best quality toy, so we bought it here.”

On December 30 Lemay’s parents spend the whole day shopping for toys in Havana to satisfy their son’s requests. In the shopping complex at the Comodoro hotel in Miramar in the western part of the city, they buy an Adidas soccer ball and a pair of tennis shoes of the same brand. At the Carlos III shopping mall they manage to find the inline skates.

“For three toys and a Neymar shirt, which we bought at a stall selling odds and ends, we spent 132 chavitos (about $140). With every passing year the selection in the stores gets worse and the toys get more expensive,” says his mother.

On this occasion the main present, sent by the grandparents from Miami, is a shiny, new bicycle. On the night of January 5 the family springs into action, hiding the toys in the least obvious places.

“We enjoy it as much as he does. My wife and I grew up at a time when people had lost hope and once a year the government ration book offered three toys,” recalls his father.

If you stroll through Havana toy stores, you will notice a lot of shoppers. Delia, an employee at the Carlos III mall, explains, “In the days leading up to January 6, toy sales exceed 20,000 convertible pesos. I don’t know where people get so much money, but they buy sophisticated toys that cost a fortune.”

An average bicycle costs around 130 CUC. A two-story doll house costs 84 CUC. The price of a metal frame pool with a water purification pump varies between 585 and more than 1,000 convertible pesos.

You have to dig through the shelves to find a toy that costs under 10 CUC. Alina and her husband, who have two children, really have to count their pennies.

“We would like to buy him the smallest electric car and the biggest race car video game, but we just don’t have the money,” says Alina, pointing to the prices. The car is driven by remote control and costs 116 CUC, and a Formula One game goes for 60 CUC.

For some time now the tradition of Three Kings Day in Cuba has been an annual occasion many parents use to try to please their children. Meanwhile, the state-run press and government institutions remain silent.

On the other hand, there has not been a return to the extremes seen in January 2001, when an outraged Fidel Castro harshly condemned a Three Kings procession, sponsored by the Spanish embassy, in which participants tossed candies through the air. Castro considered it an insult to Cuban children.

As with Christmas, Easter and the venerations of the Virgin of Charity, Saint Barbara and Saint Lazarus, the party propaganda machinery does not emphasize or promote Epiphany, a religious holiday which Christians celebrate on January 6 to commemorate the arrival of the Magi and their adoration of Jesus.

For years the military regime has tried out its own version of Three Kings Day. A few days after coming to power at the point of a gun, Fidel Castro went up in a small plane and dropped toys attached to small parachutes to children who lived along the hillsides of the Sierra Maestra and who had never had them.

As the regime became more radicalized, traditional celebrations were circumscribed or at best ignored. The government took over toy distribution and toys were rationed by the Ministry of Domestic Commerce.

During the first week of July every parent had the right to buy three toys (basic, non-basic and supplemental) for his or her child at a previously designated neighborhood store. Before paying for it, the purchase was recorded in a ration book for manufactured goods, which was similar to the ration book for groceries. Back then, people had two ration books: one for food and one for clothing.

Since the start of the economic crisis, which has lasted for twenty-six years, toys can only be purchased for hard currency or at very inflated prices in pesos. There are handmade toys, which are shoddy and plastic, but they are the only kind the poor can afford.

Gerardo, a bricklayer, has not been able to buy decent toys for any of his four children. “If anything, it will be one of those plastic trucks that private vendors sell. Or a ball,” he says. “Over time, the inequalities that Fidel promised to eliminate have gotten worse. Those of us who get screwed over are just getting screwed over more.”

Meanwhile, on the morning of January 6, as children like Lemay search for presents throughout the house, thousands of little ones only see toys in display windows. In Cuba the Three Kings do not visit every house.

A Glance at Cuba in 2015 / Ivan Garcia

Ivan Garcia, 2 January 2016 — Joel Castillo, 19, passed from expectation to frustration in 12 months. After graduating in 2014 in electronics from a technology school south of Havana, he still hasn’t been able to work in his specialty.

Ivan Garcia, 2 January 2016 — Joel Castillo, 19, passed from expectation to frustration in 12 months. After graduating in 2014 in electronics from a technology school south of Havana, he still hasn’t been able to work in his specialty.

“With the reestablishment of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States, I thought there would be better options for people. But things remain the same. And I haven’t gotten a job that fits my profile,” says Castillo.

It’s precisely the youngest who are the most disillusioned with the inertia of the olive-green Regime. A government with almost six decades in power and an executive faction whose combined age adds up to more than 300 years should have better policies for its youth.

Above all, it should take into account that Cuban society is rapidly aging and that in the fiscal year which just finished, in an irregular way, 43,059 compatriots left the Island, an increase of 77 percent in relation to 2014.

Among the irregular emigrants are the terrestrial rafters who, leaving from Ecuador, cross eight countries and different time zones, in order to try to get to the border of the U.S. with Mexico, and those who throw themselves into the sea in precarious embarkations.

If to this quantity we add the more than 20,000 visas for family reunification that the U.S. embassy in Havana grants, in 2015, around 65,000 Cubans abandoned their country in one form or another to go to the U.S.

Other thousands leave for any country. Spain, Germany, Italy, Russia, Alaska, Kazakhstan….Cuba is emptying of young and talented people. In almost all the branches of knowledge, jobs, sports or culture there exists a worrisome deficit.

For many residents on the Island, the future is to “jump the fence.” Ask a Cuban between 15 and 40 years old what his life goal is. Planning an illegal exit or finding a way to emigrate has become a national sport.

Why are Cubans leaving? It’s obvious: The economy continues to be down. It’s not a situation or a period of thin cows. It’s a stationary crisis that has extended for 25 years.

The “Special Period,” that war without the roar of tanks which began in 1990, still hasn’t ended. The inflation is more mundane, but it continues to devour the worker’s salary, and the dual currency is a liability for productivity and economic reasoning.

Economic logic in Cuba is a headache. Whoever works for the State does it eight hours a day, from Monday to Friday, and earns a salary that doesn’t exceed 23 dollars a month. And to have a dignified life, with breakfast and two decent meals, at a minimum you need 250 dollars a month.

Thanks to the taxes, the exaggerated assessments on private entrepreneurs and the poverty wages, the State pays for public health (going downhill) and a highly doctrinaire education.

But no one can repair a house or buy a car. A fundamental repair of a dwelling costs no less than 8,000 dollars. And a Peugeot 508 is worth 300,000 dollars at a State agency. Which is six lifetimes of work for a professional.

With the ration book, every citizen receives monthly, at subsidized prices, seven pounds of rice, 20 ounces of black beans, five pounds of sugar, a pound of chicken and half a pound of soy picadillo. And daily, an insipid bread roll of 80 grams.

These meager rations last for 10 days. The rest of the month you have to take out money and rack your brains. According to the autocrats’ optimistic predictions, in 2015 the Cuban economy grew 4.0 percent, but this growth hasn’t landed on the family table.

On the contrary. Pork, cheese, yogurt, milk, vegetables and fruits went up in price in the State peso markets and in the convertible money shops.

If you have only coffee for breakfast and one hot meal a day, you can understand why more than 65,000 Cubans abandoned their country in 2015. But the economic crisis can’t be summed up by the alimentary arrangement.

Every day life is more uncomfortable. Public transport is a calamity. The streets are torn up, dark and full of water. Garbage accumulates on the corners. Any personal matter occupies several hours or months owing to the lethal bureaucracy.

The hospitals have deteriorated. It’s easier to find a Martian that a medical specialist. In the primary, secondary and high schools, the low quality of teaching is alarming.

The loss of values, family violence, machismo and homophobia are reaching worrisome levels. An important segment of the population barely reads or informs itself. They master around 500 words; when they speak it sounds like they’re barking, and they gesticulate like apes.

They talk by screaming, as if people were deaf, and they listen to loud music. The lack of education has taken root with many Cubans. The most harmful thing isn’t the disorder, the precariousness and the ruins. The worst is living in a nation where you can’t plan for the future.

If you try to change the status quo by political channels, you run risks. Being a dissident in Cuba is illegal. Political parties are prohibited, except the Communist Party, and the institutions of civil society are rigorously controlled by the State.

In 2015, short-term detentions of dissidents multiplied. The beatings of the Ladies in White and peaceful opponents in a park in the neighborhood of Miramar are repeated Sunday after Sunday.

Not even moderate political tendencies are accepted, nor those that flirt with autocracy. Nor alternative press media. The economic and political situations have pushed thousands of Cubans to pack their suitcases and get far away from their country.

Despite the socialized poverty and the lack of freedoms, beginning with December 17, 2014, when Barack Obama and Raúl Castro announced the reestablishment of relations, Cuba became fashionable.

More than 50,000 Americans and famous Anglo-Saxons visited the Island. Among them Conan O’Brien, Rosario Dawson, Paris Hilton, Naomi Campbell, Rihanna, Mick Jagger, Katy Perry, Anne Leibovitz, Frank Gehry, Floyd Mayweather and sports groups from the NBA and the MLB.

Also, representatives from the Democratic and Republican parties, among them Nancy Pelosi, leader of the Democratic minority in the House of Representatives, and delegations of governors from the States of New York, Arkansas, Texas, North Carolina and Missouri, all accompanied by entrepreneurs and businessmen.

The thaw, a much-used work in the international press, has brought to Cuba tourists and people who want to take a selfie in a Havana full of propped-up houses, to ride in an almendron (old American car) and eat in a paladar (private restaurant). Ordinary Cubans see them coming and going. They form part of a thaw that is foreign to them.

Fed up with the hardships and limitations, devoid of hope for a change with the reestablishment of relations between Cuban and the U.S., and noting that in 12 months except for wifi connections in parks and public spaces barely nothing has changed, thousands of Cubans have opted to leave. For any other country.

Iván García

Photo: The photographer, Gerry Pacher, named it “Reading Newspaper,” but of the thousands of images on the Internet that are taken in Havana, we selected it to reflect the decadence of one of the most cosmopolitan cities that existed in the western hemisphere prior to 1959. Taken from the graphic report, “From the Malecón until Ernest Hemingway,” published on Taringa.net.

Translated by Regina Anavy

The Dollar Gains Strength in Cuba / Ivan Garcia

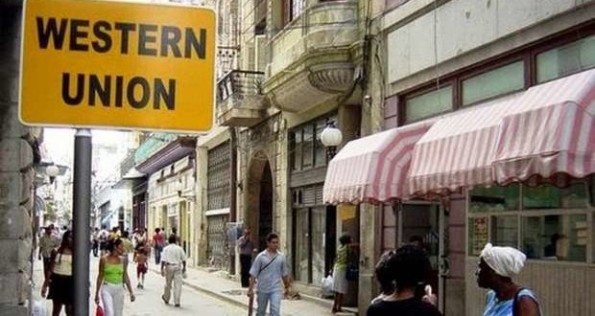

Photo: A branch of Western Union on Obispo Street, Old Havana. According to a manager of this company, 62 percent of Cuban homes receive remittances from the United States. Western Union has offices in 140 of the 158 municipalities in Cuba.

Ivan Garcia, 4 January 2016 — José Manual Cordoví keeps his savings in a rusty cookie tin. He runs a business forging windows, doors and iron in a suburb of low hovels in Arroyo Naranjo, a municipality 40 minutes by car from the heart of Havana.

Cordoví has no relatives or friends who are close to the olive-green mandarins who could give him information. But incessant rumors have encouraged him to change his savings in convertible pesos (CUCs) into U.S. dollars.

“I think that in December or January, those people (the Government) will unify the money and the Cuban convertible will disppear into thin air. They say they’ll respect the money that people have deposited in the bank. But those of us who do business under the table or keep our money under our mattresses could be screwed with a unification of money if it’s accompanied by a depreciation of the CUC,” says José Manuel.

In Havana, those who have legal or clandestine businesses prefer to bet on the dollar. While the State’s official rate is 87 cents per dollar in face of the convertible peso, people like Obdulio, an illegal jobber, say: “The green bills from 50 to 100 dollars get 95 or 96 cents. I bought others at 93 or 94.”

Every morning, six days a week, Obdulio prowls around the State exchange houses (CADECAs) in hunt of dollars.

“We independent money changers quote a higher price than the Government. Cubans who live in Miami and those who cooperate in Venezuela or Ecuador prefer to sell them to guys like me. Every day I buy 2,000 or 3,000 dollars that I sell later to a buyer at one to one against the chavito (the CUC). Since a month ago, I’ve increased the buying of dollars. Now few want to sell and many want to buy. It seems they smell something in the air,” said Obdulio, seated in a cafe on a central Havana avenue.

Doctors, engineers and sports trainers who render services in Ecuador, Venezuela or Brazil buy important amounts of dollars to get trashy goods, smart phones and home appliances that they later resell on the Island.

Also, occasional “mules” who live in Cuba and travel to the duty-free zone of Colón in Panama or a flea market in Peru or Miami buy dollars by the thousands.

But is there any foundation for the popular intuition of a coming monetary unification and devaluation of the convertible peso (which now is redeemed at one convertible peso for 24 Cuban pesos)? I asked an economist and university professor.

“In 2013, Raúl Castro’s government planned to implement the unification of the two currencies over a term of 18 months. But they haven’t accomplished it. The double monetary system creates distortions in the finances and future business deals with foreign businessmen. There are at least three exchange rates in Cuba. Certain businesses and cooperatives value the CUC at 10 pesos. Others change the CUC at one versus a dollar. And the private businesses and State exchange houses evaluate the CUC at one for 24 or 25 pesos,” says the economist.

And he adds: “Cuban finances are trapped in an unreal bubble. Our two currencies, the Cuban peso (CUP) and the convertible peso (CUC) don’t float on the international exchange market. Their appreciation is artificial, an extremely harmful State policy, since it doesn’t motivate tourists who bring dollars to change a lot of money because of the tax that Fidel Castro placed on the dollar in 2005. The low salaries in Cuba are a brake on the consumer. The unification of the money is not a caprice; it’s a measure that shouldn’t be delayed any more.”

“What could happen when the money is unified?” I asked him.

“There can be three possible scenarios. One: It could cause inflation. Two: And this is already happening, many people would change their savings or find refuge in the dollar due to little confidence in the national currencies. Three: If the unification doesn’t come preceded by a significant devaluation of the convertible peso against the peso, the monetary union would resolve little. They have taken some measures, like issuing bills of high denomination, and sectors like Public Health and ETECSA raising the salaries of their employees. But 1,500 or 1,600 pesos (65 or 70 dollars) continues to be an insignificant salary in proportion to the actual cost of living,” emphasizes the economist.

The expert considers that simultaneously with the monetary unification, they should reduce the inflated mark-ups of up to 300 percent in the State dollar (CUC) stores.

“But the key is in the low productivity which, combined with the laughable salaries, constitute a brake on the consumer, an important base for emerging from the crisis. While there are no transparent norms, a single currency and an exchange rate that is governed by the international standard, growth in the volume of investments and foreign businesses will not be spectacular,” says the university professor.

In such a closed society as Cuba, where a small group of people issue directives, it’s very complicated to know when and how the monetary unification will be carried out.

But there are interesting indications. A recent declaration by the Republican congressman of Illinois, Rodney Davis, accelerated expectations. Davis recently visited the Island on a trade mission, and he declared that Cuban officials informed him that the monetary reform would occur “within a month.”

This past May, Marino Murillo, the obese czar of the Cuban economy, offered some hints at a conference with students at the University of Havana. He told them that at the end of 2015 or the beginning of 2016, the expected monetary unification could happen.

“Don’t ask me what day because I can’t say anything, but keep everything you save in Cuban pesos,” said Murillo.

Although people like the blacksmith, José Manuel Cordoví, prefer to keep their money in dollars.

Iván García

Translated by Regina Anavy

Cuba, One Year After December 17, 2014 / Ivan Garcia

Ivan Garcia, 14 December 2015 — In a basement blackened by humidity and soot, Leonardo Santizo and two workers make cookies, candy and peanut nougat, as a private enterprise.

At the back of the room, piled up in nylon sacks, are hundreds of kilograms of unroasted peanuts, bottles of vegetable oil and all-purpose flour. On a damaged and dirty table, a thermos of recently-made coffee. While they work, they chain-smoke.

“We’ve been on our feet since five in the morning and we work until four in the afternoon. Every day we make 600 cakes, 100 packages of biscuits and 400 tablets of ground peanuts. The average pay is some 400 pesos daily. Sometimes a little more. We sell the cookies and sweets for the most part to private retail businesses,” says Leonardo.

As in every private business, they apply a double accounting and buy the raw material on the black market. “There’s a balance sheet that is rigged by ONAT (the institution that manages private work in Cuba) and another that they give the business owner, with the real gains and losses. This is the way that all the independent businesses work.”

On December 17, 2014, remembers Leonardo, “The three of us were eating lunch and listening to salsa music on a portable radio when an announcer said that President Raúl Castro would make an important speech.

“We were left without words. After so many years of rattling on about Yankee imperialism, both presidents squared off on their differences. In the afternoon we took up a collection and bought a bottle of aged Havana Club rum, and we began to make plans. We thought that things would get better and we would be able to get raw material from the North. A year has passed and things are still fucked up,” Leonardo confesses.

After drinking a bit of coffee, he continued unloading. “And we can thank God that in one day we earn what a professional earns in a month. I’m not an optimist. Those guys (the Government) don’t intend for people to live better. They want to run all the businesses themselves.”

December 17 was a watershed moment in the national life. It’s hard for Cubans to not remember what they were doing just at noon when the information bomb exploded.

Luis Carlos, a private taxi driver, was driving one of the thousand hybrid autos that circulate in Havana, with a chassis made in the Detroit factories in the 1940s to 1950s, and now rolling with motors and pieces of modern cars.

“Like everyone in Cuba, I believed certain things. I told myself, damn, now the fuckup is over and the idle talk between the Yankees and the Government. That night at home, I thought that soon fast-food restaurants would arrive; they would lower the airfare to Miami and the shops would overflow with food and rubbish from the U.S. One year later, the domino game is still going on,” says Luis Carlos.

If you chat with Cubans who have only coffee for breakfast, this is more or less the register of opinions. In 12 months they have passed from exaggerated expectations to the worst pessimism.

The balance after one year of diplomatic relations and President Obama’s road map to empower the Cuban people and extend the use of new technologies is thin.

There are 40 public plazas where, for two convertible pesos an hour (two days’ salary for a professional), you can have wireless access to the Internet.

There is a contract between the U.S. telecommunications company IDT and ETECSA (Cuba’s telecommunications company). A flurry of famous Americans have visited Cuba and little more.

For the obstruction, because in one year there hasn’t been a larger commercial interchange, the olive-green Regime blames the economic embargo, the military base of Guantánamo, Radio and TV Martí, the Cuban Adjustment Act or any other wildcard.

In those 12 months, the autocracy on the Island has only known how to complain. Or to listen only to proposals about future business with state groups, almost all of them in the orbit of military companies.

The genesis of Plan Obama, to offer a bridge with private entrepreneurs and other Cubans, has been dynamited by Raúl Castro’s government.

It’s no secret that the Island executive has no sympathy for small family businesses. In one of the first sections of the Regime’s economic bible, the so-called Economic Guidelines, it says that the State would not accept the concentration of capital in the hands of individuals.

From here comes the strategy of not permitting Cubans on the Island to invest in their own country or private workers to establish imports or trade with foreign companies.

While private businesses are perceived as nests of criminals, good intentions after December 17 remain only that.

Most Cubans feel prepared for the framework of an economic reform, access to modern capitalism and market economics.

Yohanna, an engineer, was convinced of the benefits of Marxist socialism, and she believed in the utopias of scientific communism. The night before December 17, she was walking on her knees to the entrance of the sanctuary of San Lázaro (Saint Lazarus), south of Havana, to pay a promise to one of the most popular saints in Cuba.

“I asked him that in addition to health he would bless us, since my husband and I had plans to walk to the U.S. by land from Ecuador. The following morning, after hearing the news of the reestablishment of relations, we postponed our plans thinking that things would get better. But seeing the current scenario, the only door that remains open is to emigrate. How and when I don’t know, but I’m convinced that while the same people govern, I have to get out of Cuba,” Yohanna says.

The divide between popular desire and the official narrative is evident. While the optimistic official news tells us that the country is growing, a wide segment of disillusioned Cubans feel trapped in a dead-end street with no way out.

The economy continues leaking, salaries are a joke and having two hot meals a day is an act of prestidigitization. And the Government doesn’t learn.

Iván García

Translated by Regina Anavy